John Narh

I had the opportunity to visit Marmara University for a secondment through the MARS: Non-Western Migration Regimes in a Global Perspective project from September to December 2025. My journey or perhaps, migration, since I stayed in Istanbul for more than three months, was marked by incredible experience and assistance. The following are some of my experiences.

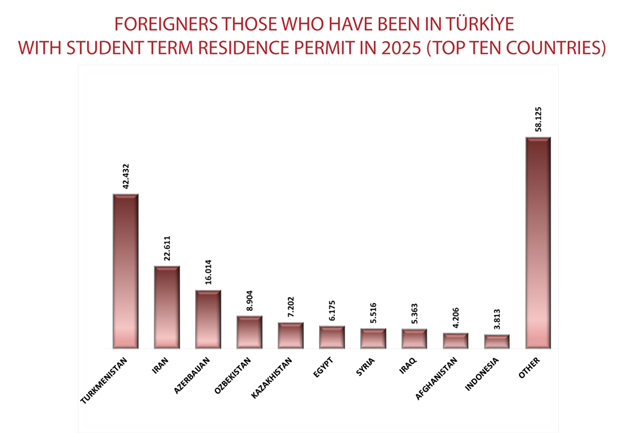

Since Ghana and Turkey have no bilateral free movement agreement, except for their diplomatic passport holders who can entre each country at will for a limited period, my migration started with visa application to the Turkey Embassy in Accra. With visa support letters from Lund University and Marmara University, the Coordinating institution for MARS and my hosting institution respectively, I was granted a 90-days visa. I had to apply for a short-term resident permit to legalise my stay for the last month, which I was granted with extra one month. It is important to mention that the documents require for the short-term permit could discourage many people from legalising their stay, especially for just a month as in my case.

Getting accommodation for a short-term stay was challenging. Yusuf Emre Kaya, the project assistant, whom I cannot thank enough, booked the Guest House at the Göztepe campus of Marmara University for me. I stayed there for a few days until I established contacts with fellow Africans in Istanbul, through whom I got a room to rent in a 3+1 apartment at Mecidiyeköy in the Şişli district of Istanbul. I prefer this arrangement because it was less expensive and it provided me with access to a kitchen to cook my food. So, I stayed in the European side of Turkey and crossed the Bosphorus each day to the office at Başıbüyük campus at the Asian side of the country. Mecidiyeköy, like other parts of Istanbul, is always bustling and constantly on the move, and Taksim Square with its famous Istiklal Street, is just 2 stops away by the Metro. In fact, I cannot agree any better with Shakhlo Safarova who also had her secondment in Istanbul and wrote that “Istanbul is a city that defies easy description”.

My host, Prof. Dr Erhan Doğan, provided an office space for me with my personal key and applied for access card to Başıbüyük campus, which Prof. İbrahim Mazlum picked for me and other visiting scholars. So, I had access to both Göztepe and Başıbüyük campuses of Marmara University. I was also assigned a Marmara University email address. My host was also supportive, not only for the progress of my research, but also, for my wellbeing.

During my secondment, I researched on forced displacement in Anglophone West Africa with a focus on displacement in Ghana. I have drafted an article with a working title, “Same fate but different outcomes? Addressing the challenges of displaced persons in Ghana”, which is earmarked for the Open Research Europe journal. Besides, I attended a joint methodology workshop, organised by my host, Prof. Dr. Erhan Doğan and his research team where I presented on the topic, “Understanding Translocality through Multi-Sited Sequential Explanatory Mixed Methods: Theory and Practice”.

John Narh presenting during the Joint Methodology Workshop. Photo credit: Yusuf Emre Kaya

I am indebted to many for my secondment. First, to the European Commission for funding the MARS project. My next appreciation goes to Lund University, particularly Chekhros Kilichova, for coordination and assistance. I am also grateful to my Director, Prof. Mary B. Setrana for endorsing my secondment. To my host and his colleagues at the Department of Political Science and International Relations, I say thank you. He has also connected me to other scholars at the department and the host for MARS at Istanbul Medipol University. Besides, my host and I are looking beyond MARS and have started working on a Memorandum of Understanding for a collaboration between the Centre for Migration Studies, University of Ghana, and the Department of Political Science and International Relations, Marmara University. Other visiting researchers I met were equally supportive. They were always available for discussion and sharing ideas. Yusuf and his colleagues, Sude, Merve and Bura were always ready to assist me with even extra-secondment activities such as exploring Istanbul, and I am grateful for their souvenirs. Hardly a day went by without me saying “thank you” to my host, Yusuf or colleague visiting scholars for a kind gesture extended to me. If “thank you” were a commodity, I would have depleted my stock of it in Istanbul from the assistance I received from my host, Professor Erhan, the research assistant, Yusuf, and fellow visiting researchers.

Comments